"Luxury beliefs" isn't a necessary idea...

(Or, I enjoy Rob Henderson's writing so much I spent nearly 6,000 words thinking about it

I think there’s a lot of good stuff in Rob Henderson’s writing. I preordered Troubled and read it that weekend. I read his Substack regularly. I have never met him, but if I had a chance to take him out to lunch and talk with him, I would.

I also think his idea of “luxury beliefs” is wrong.1

In his original essay on the idea, Henderson not only defines the term, but also lays out a series of causal stories for several ideas he labels as luxury beliefs.

And to put it plainly: I don’t see how those stories are empirically accurate.

Below, I first lay out Henderson’s definition of luxury beliefs and highlight some specific ideas he calls luxury beliefs. Then I double back to the original 2019 essay and examine his chain of reasoning from initial opinion among the upper class to effect on the lower class and try to tie each step in that reasoning to empirical information where available. In those instances where I could find such evidence, I do not get all the way from upper class idea to lower class harm.

To be clear: I believe there are (or at least may be) ideas that fit the literal definition of “luxury belief” that Henderson coined (Henderson 2019, 2024). I also think many of the ideas he labels as luxury beliefs are (sometimes? Often?) bad ideas.

But it seems to me that the causal reasoning he describes for the luxury beliefs he originally outlined is not supported empirically, which makes “luxury beliefs” seem more like a way to put down an idea without having to argue about the idea itself.2

What are luxury beliefs?

Here’s the original definition of luxury beliefs:

ideas and opinions that confer status on the rich at very little cost, while taking a toll on the lower class (Henderson 2019).

He expands upon that definition in his book, where he clarifies “rich” as the “upper class”, a group that

includes (but is not necessarily limited to) anyone who attends or graduates from an elite college and has at least one parent who is a college graduate.

He also allows that a luxury belief “often” inflicts costs on the lower class, while the initial definition requires it always do so.

So, to pull these together, according to its creator, a luxury belief is

an idea or opinion

held by non-first-generation alumni of elite colleges (and possibly a broader well-off group?)

that confer status upon that group at a low cost to that group,

while the idea may (most likely does?) inflict costs on the lower class.

Examples of luxury beliefs

Henderson mentions four luxury beliefs in his original essay: “all family structures are equal”, “religion is irrational or harmful”, “individual decisions don’t matter much compared to random social forces, including luck,” and “white privilege.”

He expands on the list in his book, and also lists a number of other ideas that college classmates of his espoused but did not seem willing to commit to:

Some would, for instance, tell me about the admiration they had for the military, or how trade schools were just as respectable as college, or how college was not necessary to be successful. But when I asked them if they would encourage their own children to enlist or become a plumber or an electrician rather than apply to college, they would demur or change the subject (Henderson 2024, emphasis added).

It is not clear to me whether these are luxury beliefs or just examples of hypocrisy. But I leave these aside for now, and focus on three beliefs for which Henderson lays out a causal path from upper class belief to lower class harm in his neologism-coining essay.

The causal effect of luxury beliefs

Henderson (2019) provides a causal mechanism for three luxury beliefs: that family structures are equal, that religion is irrational or harmful, and that success has to do more with luck than effort. When I say “causal mechanism”, I mean that he narratively describes a chain of events from upper class belief that leads to lower class harm.

I produce each of these narratives below, then try to state them precisely in ways that can be examined empirically. Then I try to find empirics to back those steps up. Spoiler alert: I think I largely fail to find supporting evidence, but that’s not just for me to decide.

Family structures are equal

For “all family structures are equal”, he writes:

Relaxed attitudes about marriage trickle down to the working class and the poor. In the 1960s, marriage rates between upper-class and lower-class Americans were nearly identical. But during this time, affluent Americans loosened social norms, expressing skepticism about marriage and monogamy.

This luxury belief contributed to the erosion of the family. Today, the marriage rates of affluent Americans are nearly the same as they were in the 1960s. But working-class people are far less likely to get married. Furthermore, out-of-wedlock birthrates are more than 10 times higher than they were in 1960, mostly among the poor and working class. Affluent people seldom have kids out of wedlock but are more likely than others to express the luxury belief that doing so is of no consequence. (Henderson 2019)

Restating his argument less beautifully but (I hope) more precisely:

In some earlier time period (the 1960s or shortly thereafter), there is greater support for non-two-parent families among the upper class than among the lower class or, at minimum, a positive relationship between educational attainment and support for non-two-parent families.

The support for nontraditional families among everyone else (i.e., the lower class) increases over time to match that of the upper class.

The behavior of the lower class changes to match the new social norm, which leads to worse outcomes for the lower class (because non-two-parent families have worse outcomes, and this family-structure-and-child-outcomes relationship is causal).

Note that for the entire causal chain to hold (and thus fit the definition of a luxury belief), the upper class has to be the first to adopt ideas supporting nontraditional families, then those ideas spread among the lower class, and finally the behavior of the lower class changes (in deleterious ways) among the lower class.

Evidence for his claim, then, would be data from the 1960s and 1970s that initially show upper class opinion holding more relaxed or skeptical views of marriage than the general population, followed by the general population adopting those views at some point thereafter, followed by an increase in single-parent households among the lower class.

Sadly, I could not find publicly available data of high quality that stretched back to the 1960s. While I suspect Gallup has such data, publicly they post only toplines on questions about marriage extending to the early 2000s.

I did, however, encounter previous research that examines something similar to this question. Thornton (1989) uses a combination 1960s data from the Study of American Families (measuring a panel “of mothers and children … from the 1961 birth records of the Detroit Metropolitan Area”)3, the Monitoring the Future survey (a probability sample of high school seniors starting in 1976), and the General Social Survey to examine “three decades of changing norms and values concerning family life in the United States.”

I don’t want to fail to present evidence consistent with Henderson’s thesis: as Thornton says in the abstract, “the analysis indicates that the changes in family attitudes and values were particularly striking during the 1960s and 1970s.” To be clear: lots of beliefs changed in the 1960s. But I want to focus on the data from the Study of American Families about divorce as it’s (a) from the 1960s and (b) directly addresses Henderson’s claim. Here’s the table from Thornton:

In 1962, 51% of respondents already disagree with the statement that “when there are children in the family, parents should stay together even if they don’t get along.” If we treat the Study of American Families as lower class and not upper class opinion, we start the 1960s with a slim majority of the population holding “relaxed attitudes about marriage.” What changes by the (near) end of the 1970s is that this position goes from slim majority to overwhelmingly preferred.

Is it possible that, were we to have access to the individual-level data from these surveys, we would find evidence that upper class opinion (for some definition of upper class that we could construct within the survey) was even more favorable toward divorce than the rest of the population?

Sure it is.

But that’s something to be demonstrated, not to be taken on faith. If there is evidence that “during this time, affluent Americans loosened social norms, expressing skepticism about marriage and monogamy” and that “this luxury belief contributed to the erosion of the family,” this isn’t it.

Now, I’d call the 51% in 1962 not great for the first step in the causal story, but it’s hardly decisive. It’s possible that better evidence exists but this isn’t it. What else can we find?

Well, the General Social Survey is accessible going back to 1972. And it has two questions that touch on, but aren’t exactly, “family structures are equal.” But they’re pretty close—the question asks whether respondents agree or disagree that a single mother (or a single father) can raise kids as well as a couple. Not bad, right?

Well, mostly right. They have two weakness from my perspective:

They do not speak to the nature of single parenthood. Henderson’s focus appears to be on children born to unmarried couples or divorce, not widowhood (i.e., parental choices, not random circumstances). This question is less precise than he might mean.

Henderson starts the causal chain in the 1960s, while this question was only asked in 1988 and 2022. As such, we fail to capture nearly 30 years of the story with these questions.

Those weaknesses stated, I think that Henderson’s causal chain implies:

In 1988, there is net support (agreement less disagreement is positive) for each statement among the upper class.

In 1988, net support for the statement is higher among the upper class than among everyone else.

In 2022, net support for each statement has risen among the lower class to converge with upper class opinion.

To examine the links in this causal chain empirically, it’s important to define terms. Here are mine:

Upper class – respondents who are in the top 10% of educational attainment for their survey year using the variable ‘educ’ and who have at least one parent who has at least four years of college (maeduc and paeduc).4 [4]

Family structures are equal – agreement with the sentiment that “a single mother can raise kids as well as a couple” or “a single father can raise kids as well as a couple.”

Here’s the data:

It is clearly the case that there is greater support for both sentiments on family structure among the upper class than among the lower class in 1988. But net support—agreement less disagreement—for both positions is nonexistent among the upper class in 1988. Thus, this is not something that, on balance, was an “upper class belief”, and we can reject the first implication of the causal chain.5

As for the second implication, it is also clearly the case that net support for both statements is higher among the upper than the lower class in 1988. The difference is smaller for single mothers (9% difference) than fathers (17% difference), but both are present.

The third implication is also supported in the data; we shift from a difference in net support of 9% and 17% in 1988 to 3% and 5% in 2022.

That the third result, though, is consistent with the model is dwarfed by the within-group changes between 1988 and 2022. In 1988, there were as many upper class people opposed to the idea that single moms were as good as couples for raising children; in 2022, three times as many upper class respondents supported that idea as opposed it. And that’s also true for everyone else.

So what the heck happened?

Per Henderson’s causal chain, what happened was that first the upper class became net supportive of single parenthood, then the lower class did, and finally the lower class’s behavior changed. And yet:

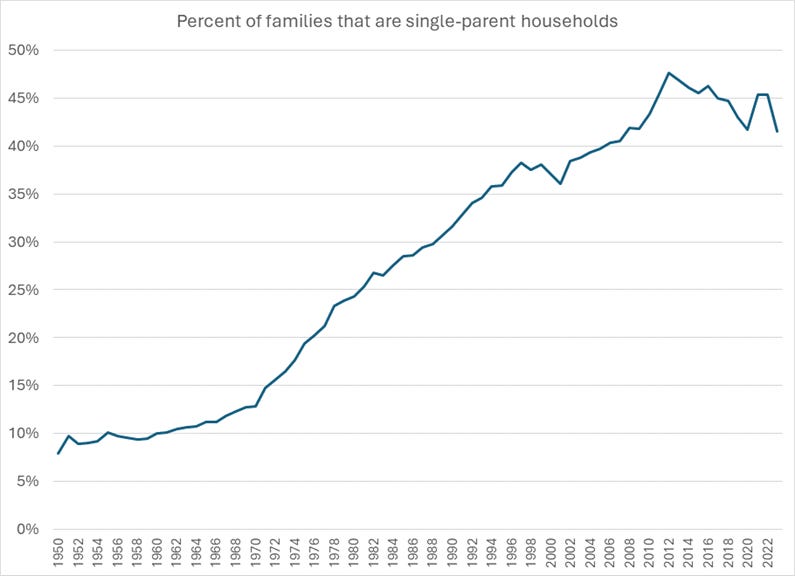

This graph shows the percentage of single parent families (as a percentage of all families with children) from the Current Population Survey (Table FM-1). Visually, it appears the sharpest increase in single parent families seems to be from about 1970 to about 1998. 1988 is pretty close to the middle of that period. How can it be that the upper class belief that all families are equally good at raising children percolate down to harming the lower class by changing their behavior around family formation… if that belief wasn’t held by a majority of the upper class and hadn’t percolated down to the lower class by 1988?

My answer is this: I don’t know. Maybe, somewhere, upper class beliefs did start it all and the data just aren’t there. I think there’s a possibility that causation runs from beliefs to behavior as Henderson argues.6 It’s just that there are not strong data (that I could find) supporting Henderson’s claim that this change in attitudes started with the upper class, was adopted by the lower class, and thus affected lower class behavior. And as such, I don’t see how it fits the definition he created.

Religion is irrational or harmful

Here is what Henderson (2019) says about religious belief:

Another luxury belief is that religion is irrational or harmful. Members of the upper class are most likely to be atheists or non-religious. But they have the resources and access to thrive without the unifying social edifice of religion.

Places of worship are often essential for the social fabric of poor communities. Denigrating the importance of religion harms the poor. While affluent people often find meaning in their work, most Americans do not have the luxury of a ‘profession.’ They have jobs. They clock in, they clock out. Without a family or community to care for, such a job can feel meaningless. (Henderson 2019)

Note that, unlike family structure, Henderson doesn’t lay out a story on how the upper class belief harms the lower class. So I’m going to try making the family structure story fit here:

In some earlier time period, there is greater support for the idea that religion is harmful among the upper class than among the lower class.

Over time, the belief of the lower class gradually comes to match that of the upper class.

The behavior of the lower class changes to match the belief, which leads to worse outcomes for the lower class (because religion is a “unifying social edifice” which provides a “family or community to care for” and creates meaning in people’s lives).

In my restatement, causation flows from an upper class belief, to that belief spreading, to that belief having an effect on lower class behavior.

I find this story challenging, and maybe it’s not what Henderson has in mind. As Henderson states, the upper class is more likely to be non-theist than the lower class. But that is true right now: right now, people with higher levels of education are less religious than everyone else.7 From the Pew Research Center (2017):

How has the greater nontheism of the upper class (in the Pew data, college graduates broadly) affected the belief of the lower class? Is it that, if a majority of college graduates said religion is very important, then even more respondents with a high school education or less would agree with the same sentiment?

But this is one point in time; perhaps, as with family structure, the story is best appreciated over time. The General Social Survey also includes questions on religious belief. Using the same definition for upper class as stated above, and defining nonbelievers as those who choose ‘none’ on the religion question (‘relig’), here’s the change in nontheism since the 1970s:

Recall that the upper class is a small subsample, so the smaller number of observation results in a noisier sequence. But in no year do a majority of the upper class profess atheism. As of 2022, nearly 45% do so, but that means half continue to profess a belief in some religion. And aside from the late 1980s, it sure looks as if the upper class is not consistently much more nontheist than everyone else until very recently.

Perhaps religious behavior first collapsed among the upper class, but not the lower class, and that change in participation in religion is what causes the subsequent collapse of religious behavior among the lower class. The General Social Survey also has a question on religious attendance (‘attend’). Here is the percentage of respondents who attend religious services “nearly weekly” or more, by year and social class:

In more years than not (about 60% of the years), the upper class is less likely to be regular church attendees, but neither the upper nor lower class begins the period with a majority of regular churchgoers. And indeed, since the 1990s, it seems the two classes’ behavior is on a similar path.

Thus, we have both classes having similar levels of stated belief and religious attendance, without the upper class clearly leading the lower class (perhaps in attendance in the 1970s and 1980s?). If one wants to argue that this behavior is less positive for the lower class than for the upper class, I can understand that. But I do not see in these data the beliefs or actions of the upper class leading or causing the behavior of the lower class. Indeed, if one focuses on the Pew data rather than the General Social Survey, how is the upper class’s belief about religion harming the lower class if the lower class continues to believe (and more importantly, behave) contrary to the upper class?8

The Role of Luck vs Effort

On this topic, here again is Henderson (2019):

Then there’s the luxury belief that individual decisions don’t matter much compared to random social forces, including luck. This belief is more common among many of my peers at Yale and Cambridge than the kids I grew up with in foster care or the women and men I served with in the military. The key message is that the outcomes of your life are beyond your control. This idea works to the benefit of the upper class and harms ordinary people.

It is common to see students at prestigious universities work ceaselessly and then downplay the importance of tenacity. They perform an “aw, shucks” routine to suggest they just got lucky rather than accept credit for their efforts. This message is damaging. If disadvantaged people believe random chance is the key factor for success, they will be less likely to strive.

It seems to me that the causal mechanism I’ve set out above works here as well:

First the upper class adopts the view that success is primarily due to luck and not effort. 2.

Gradually, everyone else comes to hold a similar view.

Finally, the behavior of the lower class changes to match this new belief, which leads the worse outcomes for the lower class (because, if not predominantly due to effort, success is at least positively related to effort).

Though, to be fair to Henderson, he does not say that this has occurred, even in the original formulation. Rather, he says if the lower class were to adopt this view of success he encountered at university, then it would harm the lower class’s well being.

But does the upper class actually hold this view?

Henderson (2022) presents evidence that there is a difference in this belief between the upper and lower class in general over time and around the world: Daniels and Wang (2019) use several waves of the World Values Survey and show that, conditional on several other correlates, respondents who have higher self-reported relative income and higher self-reported social status are more likely to agree that success is due to luck rather than hard work.

Here is my confusion: this study pools data both from around the world and across time (from 1990 to 2014). Assume, for the moment, that the results are not time varying. In that case, what’s the problem? The beliefs of the lower class have not changed, and therefore cannot have changed their behavior yet. They’re still striving! And the belief doesn’t seem to have harmed the upper class at all. Maybe he raises this as a cautionary tale—if the upper class continues to hold this belief, then in the future it will negatively affect the beliefs and effort of the lower class?

It is possible, however, that longitudinal data shows the upper class preceding the lower class to the present moment, so that this is not yet causing harm, but will cause harm in the future. Unfortunately, the General Social Survey has only one question on this topic, and it was asked only in 1996 (‘mostluck’—do you agree or disagree that good things are mostly luck?).9 But the World Values Survey (Inglehart et al. 2014) is publicly available. Here is the question that Daniels and Wang use:

How would you place your views on this scale? 1 means you agree completely with the statement on the left; 10 means you agree completely with the statement on the right; and if your views fall somewhere in between, you can choose any number in between. In the long run, hard work usually brings a better life, OR Hard work doesn’t generally bring success – it’s more a matter of luck and connections.

The World Values Survey asked this question in the United States in 1995, 2006, 2011, and 2017. Low values indicate agreement with the idea that hard work pays off, while high values indicate agreement with the idea that luck drives one’s outcomes.

The survey also records educational attainment, but only records parental educational attainment in 2017, and also only codes educational levels beyond a university degree in 2017 as well. As such:

for upper class, I use attainment of a 4-year degree or higher, and

for “luck”, I code any respondent with a 7 or higher on the 10-point scale as agreeing that luck determines success.

Here’s what the U.S. observations from the World Values Survey show:

In no wave of the survey do more upper class respondents than lower class ones agree with the idea that success is mostly a matter of luck. That, however, does not directly contradict Daniels and Wang nor Henderson’s interpretation of them, as they control for a number of covariates and Henderson places emphasis not on education (as was included in the expanded luxury belief definition) but on relative income or social status.

Before I dig into two papers to get the list of controls and run a couple of ordered logits with wave-education fixed effects (as Daniels and Wang did), here’s the same graph, but replacing upper class with those who choose “upper class” as their self-reported social class:

Now we see a pattern that is at least partially consistent with Henderson’s argument: more upper class respondents say success is due to luck than do non upper class people (note that I’m putting all non-upper-class people together here). But again, I do not see how this belief can cause harm to the lower class if the lower class itself does not adopt it (which it clearly hasn’t, at least not as of 2017) and a supermajority of the upper class disagrees with it.

An alternative way to think about these particular beliefs

I do not want to deny that many people—including (if not especially) upper class people—espouse views for the purpose of raising their status. I’m just not convinced that the luxury beliefs model is the best way to think about such beliefs in general, or about the specific beliefs we’ve covered here.

I also do not think it entirely fair to just say, “well, I think this is wrong,” and not at least take a stab at an alternative explanation, though I suspect I have spent considerably less time than Henderson considering these particular beliefs, the concept of status, and the idea of luxury beliefs. Thus, I offer two ideas in the spirit of being a good sport and am quite welcome to disconfirming evidence (as I am offering no evidence favoring them in the first place).

Many of the items that Henderson would characterize as “luxury beliefs”, and in particular the claims about family structure and the role of luck, strike me as an unwillingness to pass judgement on others’ choices. While I think one could make this about status again, I see this mostly as an issue of moral relativism. I have, to be fair, no evidence whatsoever for this position, and I hold it very weakly.

I am more prone to see belief change following, rather than leading, behavioral change. First people do something differently (due to a random shock, due to a change in relative prices, what have you), and only later do they reconfigure their beliefs around this new behavior. Again, I have the same (lack of) evidence for this position as my previous one.10

Conclusion

I am not the first to critique Henderson’s idea of luxury beliefs. Indeed, Samahita (2024) formalized Henderson’s definition and tested it in two online experiments; she finds that they signal college attendance but not broader concepts of social status (i.e., economic status).

So why bother?

I wrote this because I think Henderson is a clear and honest thinker who believes in empiricism. He shares three links of neat empirical findings in the social sciences at the end of many of his Substack posts. And while I find many of his ideas useful, I don’t think this one fits the data very well. Thus, I have written up this critique in the hopes that he (and people who read him and use the term “luxury belief” in their day-to-day lives) will engage with it and either (a) demonstrate the idea empirically with better evidence, (b) show me the error in my understanding of the idea, or (c) revise the concept of luxury beliefs in a way that better fits the available data.

For example, if by luxury beliefs, Henderson means:

ideas and opinions that are held relatively more among highly educated people but that, if sincerely held and acted upon by everyone else, would do everyone else harm.

then I withdraw my critique.11

But if that is true, then it doesn’t matter whether highly educated people believe it or not (to gain status or otherwise) unless the upper class believing the idea causes the lower class to act on the belief.

And even that part doesn’t matter unless the last step (the effect of the action on some outcome that matters) is causal. Because if acting on those beliefs won’t lead to bad outcomes for the lower class, and thus the belief can’t serve as a signal, because it’s just as cheap for the lower class as it is for the upper.12

Otherwise, the idea of “luxury beliefs” as espoused by Henderson above now reads (to me anyway) more like an ad hominem, in which we’ve replaced determining, e.g., how much family structure impacts children in a causal manner with saying it’s hypocritical for an upper class married parent to say single parenting is okay when they’d never choose it for their own family. And from what I’ve read from Henderson, he strikes me as the kind of person who’d rather engage people on the merits of the main issue—whether behavior consistent with that belief is helpful or harmful.

References

Daniels, J., & Wang, M. (2019). What do you think? Success: is it luck or is it hard work? Applied Economics Letters, 26(21), 1734–1738. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2019.1593930

Henderson, Rob (20 February 2024). Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class. Gallery Books.

Henderson, Rob (12 June 2022). “Luxury Beliefs are Status Symbols.” Retrieved from

Henderson, Rob (17 August 2019). "Luxury Beliefs Are the Latest Status Symbol for Rich Americans". NY Post.

Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.). 2014. World Values Survey: All Rounds - Country-Pooled Datafile Version: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

Pew Research Center (26 April 2017). “In America, Does More Education Equal Less Religion?” Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/04/26/in-america-does-more-education-equal-less-religion/

Samahita, Margaret (May 15, 2024), “‘Luxury beliefs’: Signaling through ideology?” WP24/10, University College Dublin School of Economics.

Thornton, Arland. (1989). “Changing Attitudes toward Family Issues in the United States.” Journal of Marriage and Family, 51(4): 873-93.

I once worked in politics and heard someone say, “no good political argument starts with ‘yes, but...’”. In the same way, I suspect no good compliment starts with, “you’re great! But…”. I hope the critique itself reads as a compliment: I would not spend this much time on an idea from someone whom I thought was an idiot or an idealogue.

Note that the empirics I provide here are fairly rudimentary. I am open to examining all of this more rigorously if it would be of value to others. Again, I’m kind of a fan, or I wouldn’t have spent 5,000+ words on the topic.

The Study of American Families is not nationally representative nor is it a study of elite opinion using Henderson’s narrow definition. That said, as of 1959, median family income nationally was about $5,660 nominal, while in Detroit it was $6,825. While I treat average responses from this survey as lower class or general opinion, I think one could make a case for this being closer to upper class for its time, which favors Henderson’s argument.

Undoubtedly this includes many people did not attend an elite college or university. As such, I am open to alternative specifications.

To be clear: I find Henderson’s more limited definition of upper class intuitively appealing. I just can’t operationalize it, especially in historical data. There’s just not enough elites under his more limited definition to show up in a national survey.

Given how split this definition of elite is and the overall direction of difference along educational attainment, it is possible that if we could separate out Henderson’s literal definition of elite from my more expansive version, we’d find net support for both of these positions among this more precise elite.

But the one thing I did try—changing the cutoff for educational attainment from the top 10% to the top 5% by years of schooling—resulted in an elite that was even less supportive of both propositions. That’s not decisive evidence against Henderson’s claim, as I do not think the General Social Survey’s education question really captures the group that Henderson means by “the elite.” But it’s certainly not supportive evidence, either.

If anyone were interested, there are the data from the graph above, plus data from Gallup for the 2000s on (a) whether divorce is morally acceptable and (b) whether out-of-wedlock childbearing is acceptable. I could try putting that together into a vector autoregression to see if beliefs Granger-cause behavior or vice versa, if there are any interested readers of such results.

To be fair: 2014 is not right now, nor was it right now in 2019. But it’s also the first result when one searches Pew Research as of July 2024, so I offer it in that spirit.

One possibility is that we call something a luxury belief not based on actual harm of the belief, but harm if the belief were held and acted upon by the lower class. That fits the idea of signaling. But we’ll come back to that in the conclusion.

Unlike the more recent data that Henderson cites, using the definition of elite described above, I find that 1.6% of upper class respondents agree that good things are mostly luck, while 87% disagree. For the lower class, 18% agree with the statement, while 75% disagree. So there’s more agreement with the idea that luck drives good outcomes among the lower class, but both classes overwhelmingly disagreed with that sentiment back in the 1990s.

Though, for this possibility, do note that I started to tinker with this idea above in a footnote. I am far from sure that the Granger causality tests would favor this position. While this is something I wanted to share, I am already much less convinced of it than when I dreamt it up.

Yascha Mounk has offered up a re-definition of luxury beliefs as well that, at first glance, significantly sidesteps my discussion above. I have not had a chance to digest it fully.

Now, if we focus on policy beliefs, then it’s not about acting on the belief but whether the belief gets put into law or regulation. But, as Bryan Caplan already explained, no one of us is so decisive in politics that our ideas become law, so we can believe whatever we want to our little heart’s content. There is no pathway from our beliefs to policy outcomes strong enough to make us personally face the costs.

Very interesting, and makes me want to read his work, but I had a hard time swallowing the definition of "upper class"/"rich" as "a group that includes (but is not necessarily limited to) anyone who attends or graduates from an elite college and has at least one parent who is a college graduate." To me, that's a solid middle/upper middle class identifier, so he's lumping middle with upper class using that definition. Upper class/rich to me has a stricter definition of wealth (and income to savings ratio) than is captured there. (Minutiae)