I spent my last post criticizing an idea of Rob Henderson’s. In this post, I want to use his definition of social class and try to make it as precise as possible. I hope, in doing so, it will demonstrate why we probably want to use a less restrictive definition of upper class when talking about social class.

Anyway, here’s Henderson’s (2024) definition of upper class:

The upper class includes (but is not necessarily limited to) anyone who attends or graduates from an elite college and has at least one parent who is a college graduate. [1]

I’m going to start by ignoring the “not necessarily limited to” part and try to get a back-of-the-envelope estimate of the size of the non-parenthetical definition. I’ll then tie that to self-identified social class data from national surveys and see if we can draw firmer boundaries around Henderson’s education-based upper class.

My whole point in doing this, to be clear, is that I think this is an interesting and relevant set of people to think about, but I think it misses a whole lot of people whom everyone else in the country would classify as “upper class” (whether they would themselves or not). And, per my last post, when you mix in those other people (the “should-be-upper-class”?), a lot of the beliefs (if not behaviors) of that group are a lot less monolithic than the narrower definition implies.

So, let’s get started!

Who’s this elite, anyway?

Per Henderson, there are two parts to being elite:

1. Attending an elite college, and

2. Having a college graduate as a parent.

“College” is a pretty well-defined concept, but what’s an ‘elite’ college? One definition I see used in research is “Ivy Plus”, which is the Ivy League and another set of 10 or so highly selective national research universities. But if I stick with that definition, here’s what we get for one measure of the upper class for one age cohort of the United States:

This table adds up the enrollment of all non-first-generation students at Ivy Plus institutions and divides the sum by either all 18-to-24-year-olds who attend a four-year institution, or all 18–24-year-olds.[2] As shown, the upper class is about 1.2% of all college-going students by this definition, or a shade under half a percent of all young adults. As few students get to attend institutions like these for undergraduate study after age 24, this is a decent estimate of Henderson’s upper class.

Is that reasonably sized? Well, let’s compare it to another measure of social class: self-reports. Here’s some recent data from Gallup on self-identified social class:

According to Gallup, about 2 percent of U.S. residents self-identify as upper class. We’re getting about a fifth of that number (non-self-reported, mind you) from this educational definition. If we assume that’s the “true” size of the upper class, who else could we add?

Say we throw in the enrollment of the top 50 liberal arts colleges from U.S. News and World Report (that’s from Williams to Whitman College)? That’s another 84,745 students in total before adjusting for first generation status. After digging through all their websites and removing the fraction of first-generation students, that gives us 72,411 new members of the upper class.

Now add the enrollment of all the top 50 national universities as well (less those already counted as Ivy Plus), and remove all first generation students from our count as well. The top 50 non-Ivy Plus national universities have 859,508 students. Because many of the top 50 national universities are large state schools that actively encourage first generation students (e.g., the University of California system), I looked up first-generation percentages for all of them. Taking their total enrollment of 859,508 and subtracting out first-generation students, these institutions add another 652,932 souls to the upper class.[3]

All in, if we redefine upper class as:

“anyone who attends or graduates from a Top 50 National University or Top 50 Liberal Arts College as measured by the U.S. News and World Report higher education annual rankings, and has one parent who is a college graduate.”

that puts us at 835,202 out of 30,114,169 18-to-24-year-olds in the upper class, or about 2.8 percent. Since very few people aged 25 and up will get the chance to join the upper class by this definition, we can think of this group getting produced within each age cohort, with slightly more people added now than in the past.

I’m reasonably comfortable with that list as the definition of upper class. It’s almost 50 percent more than self-identify, but relative to the margin of error on a single poll, it’s really close.

Thus, it seems to me that my reworked definition is a good example of what Henderson means by the upper class. But I also think fleshing out Henderson’s definition of upper class this way speaks to his implied cultural idea of the upper class in terms of their left-wing ideological tilt.

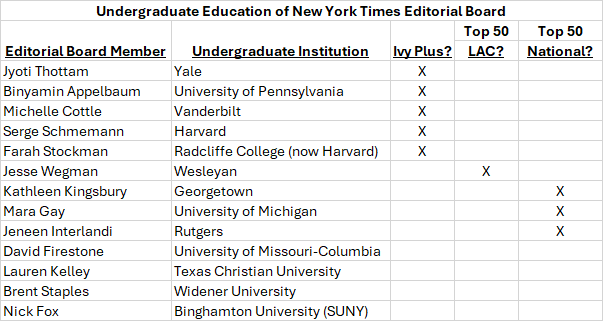

For example, here’s the undergraduate education of the editorial board of the New York Times, the second-highest circulating paper in the U.S.:

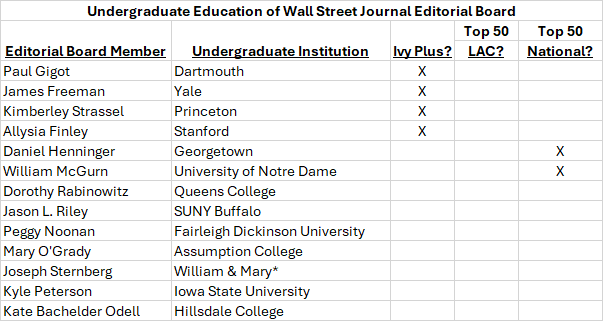

All but three members of the editorial board are members of the upper class by my definition. And over a third come from just the Ivy Plus, a set of institutions that only 1.5 percent of all college going folks ever attend. Inasmuch as the Times is a culture-defining journalistic endeavor, it’s pretty clear that it is led by the upper class. In contrast, here’s the education of the editorial board of the highest circulating paper in the U.S., the Wall Street Journal:

The Journal has about the same percentage of Ivy Plus graduates as the Times, but what is striking is that less than half of the editorial board members at the Journal attended an elite college or university (by my amended definition of elite, that is).[4] And yet, the Journal is the highest circulating newspaper in America.

I suspect no one will object to me calling the Times a left-leaning paper and the Journal a right-leaning paper. But are we really going to say that the Editorial Board of the Times is made up of the upper class… and the Board of the Journal isn’t? Maybe that’s the point of this definition—that the heights of educational attainment are left-leaning (and, to Henderson, left-leaning in ways that are harmful to the lower class). And yet I think that, at least for me, the purely educationally based definition misses something big: material well-being. That is, people who have been successful in their careers, or who make (or have) a lot of money. And that’s what we’ll dig into in our next installment.

[1] Some readers (well, one reader? A reader!) suggest that definitions of social class should tie more to material resources—wealth or income. I’ll just say: we’ll get to that. Stay tuned!

[2] And before you ask: no, the years do not perfectly line up. Also, for most colleges, I’m using the most recent cohort’s first-generation percentage, which (according to the press releases I’ve pulled them from) are higher than in previous years. And Rice University didn’t provide a percentage of first-generation students, so I assumed zero (I know: it’s definitely not zero.). So this is a back-of-a-wet-envelope-at-a-bar estimate.

[3] I was originally going to just apply the average first-generation percentage from the Ivy Plus to the liberal arts colleges as-is, and then double it for the national universities (as many are large state schools that actively encourage first-generation students to apply and attend).

[4] William and Mary is just outside the list of top 50 national institutions, and has been in the top 50 repeatedly in the past.

Thanks for expanding on this :)